That simple idea—placing light where you do things—changes everything. It moves us away from just lighting a room to lighting a life. But I know you have more specific questions. You’re probably wondering about distances from walls, how to apply this in a living room, or how many lights you actually need. Let’s break it down, step by step, so you can plan your next project with confidence.

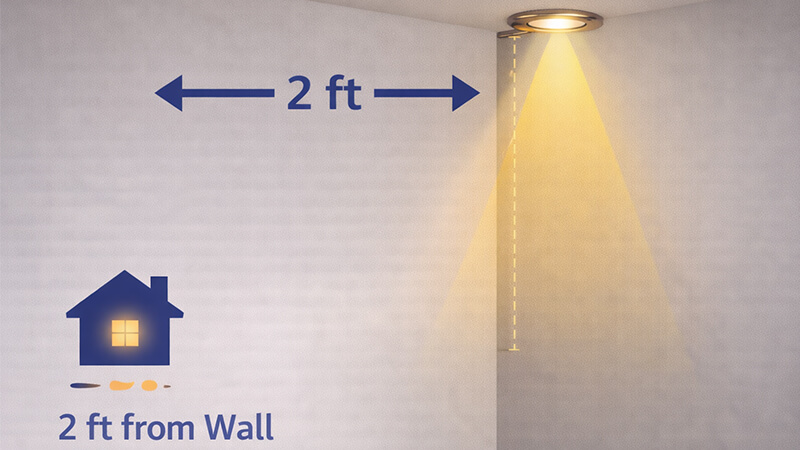

How far should a downlight be away from a wall?

Placing downlights too close or too far from a wall is a common mistake. Too close creates harsh "scallops" and glare. Too far leaves key areas in the dark.

For general ambient light, place downlights 70-90 cm (about 30 inches) from the wall. To highlight artwork, aim for a 30-degree angle, which often means placing the light 50-70 cm from the wall, depending on your ceiling height. This prevents glare and lights the object beautifully.

The right distance from a wall really depends on what you want the light to do. Are you lighting the wall itself, or are you lighting a task that happens near the wall? This is the most important question, and it’s where many people go wrong. They see dramatic "scalloping" light effects in magazines and try to copy them, but this often creates uncomfortable glare in a real home. As a manufacturer, I’ve seen countless lighting plans, and the best ones always start with purpose.

Lighting the Wall: Washing vs. Grazing

Sometimes, the wall itself is the feature. You might have beautiful artwork or a textured surface you want to show off.

- Wall Washing: This technique creates a smooth, even layer of light on a wall, which can make a room feel brighter and more spacious. To achieve this, you need to place your downlights further from the wall. A good distance is about 80 cm to 1 meter. You should also space the downlights a similar distance apart from each other. This creates a soft, uniform wash.

- Wall Grazing: This is the opposite. You place the downlights much closer to the wall, typically 30-50 cm away. This creates light that hits the wall at a very steep angle, which is perfect for highlighting texture. Think of a stone fireplace or a brick feature wall. The light rakes across the surface, creating shadows that reveal all the detail. Be careful, though. Using this technique on a standard plaster wall will highlight every single imperfection.

Lighting a Task Near the Wall

This is where my core philosophy of "action points" really shines. Most of the time, the light near a wall is for a task. The most common example is a kitchen counter. The biggest mistake is to center the downlight over the middle of the counter. When you stand there to chop vegetables, your head blocks the light, casting a shadow directly on your workspace. The solution is simple: position the downlight so it’s centered over the front edge of the counter, about 60-70cm from the wall. This puts the light in front of you, not behind you, and illuminates your task perfectly.

| Lighting Goal |

Distance from Wall |

Purpose |

| Task Lighting (Counter/Desk) |

60-70 cm |

Illuminates the work area, not the back of your head. |

| Wall Washing |

80-100 cm |

Creates a bright, even feel, making the room seem larger. |

| Wall Grazing |

30-50 cm |

Highlights texture on surfaces like brick or stone. |

| General Ambient |

70-90 cm |

Provides overall room light without creating harsh wall scallops. |

Where should downlights be placed in a living room?

Living rooms are complex spaces with many uses. A simple grid of downlights often fails to create a comfortable or functional atmosphere, leaving it feeling flat and uninviting.

In a living room, place downlights based on activity zones, not a rigid grid. Position them to highlight features like artwork (accent lighting) and to illuminate tasks like reading (task lighting). Layer this with lamps and always use dimmers to create a flexible, comfortable mood.

A living room is for relaxing, reading, watching movies, and entertaining guests. A single, uniform lighting approach cannot work for all these activities. The biggest mistake I see from specifiers is a symmetrical grid of downlights. It’s an easy plan to draw, but it rarely makes a space feel good. I always advise my clients, many of whom are experienced professionals like Shaz, to abandon the grid and think in layers.

Step 1: Forget the Grid and Identify Your Zones

First, look at the living room layout. Where is the main sofa? Where is the television? Do you have a favorite chair for reading? Do you have bookshelves or artwork you want to be a focal point? Thinking in zones instead of a grid is the first step to great lighting design. The grid approach often leads to what I call "ceiling acne"—too many lights in a pattern that serves no real purpose other than symmetry. The result is often glare in your eyes when you’re trying to watch TV or a flat, boring light when you’re trying to relax.

Step 2: Light the "Action Points" and Features

Now, let’s place lights specifically for those zones, using my "action point" principle.

- Reading Nook: For a favorite reading chair, don’t put a light directly overhead. This will cause glare on the page. Instead, place a narrow-beam downlight (around 24-36 degrees) slightly in front and to the side of the chair, so the light falls across your shoulder onto the book.

- Coffee Table: This is often a central point for conversation or games. A single, wide-beam downlight (60 degrees or more) centered over the coffee table can provide great functional light. It must be on a dimmer so you can turn it down when you want a softer mood.

- Artwork and Features: Use adjustable (gimbal) downlights to aim light at your features. Place the downlight so that the beam hits the center of the artwork from about a 30-degree angle. This is the museum standard for minimizing glare from the glass or canvas.

Here is how you can think about layering your living room lighting:

| Light Layer |

Purpose |

How to Achieve with Downlights |

| Ambient |

General, overall illumination for moving around safely. |

A few well-spaced, wide-beam downlights on a dimmer. |

| Task |

Focused light for specific activities like reading. |

Narrow-beam or adjustable downlights over chairs or desks. |

| Accent |

To highlight art, plants, and architectural features. |

Adjustable (gimbal) downlights aimed at specific objects. |

| Decorative |

To add style and warm pools of light. |

This layer is for your floor lamps, table lamps, and pendants. |

By combining these layers, you create a dynamic, flexible, and comfortable space that can adapt to anything you want to do.

How many downlights should you have in a room?

People are often confused by complex formulas for calculating the number of downlights. This leads them to either install too many, creating a harsh environment, or too few, leaving dark spots.

Instead of using a formula, determine the number of downlights by the room’s function. Identify each task and feature that needs light, like a reading chair or artwork. Place one well-chosen downlight for each specific purpose. This "less is more" approach is far more effective.

In my years of manufacturing and designing lighting solutions, I’ve found that the old, common formulas often do more harm than good in residential spaces. The classic "lumens per square meter" calculation is a blunt tool that fails to produce a comfortable or well-designed space.

The Problem with the Square-Meter Formula

The standard formula (Room Area x Target Lux = Total Lumens Needed) seems scientific, but it ignores the most important factors in a real-world room.

- It Ignores Surface Colors: A room with dark wood floors and navy blue walls absorbs a huge amount of light. It needs more lumens to feel as bright as an all-white room. The formula doesn’t account for this.

- It Ignores Function: It treats a hallway the same as a kitchen, just with a different target lux number. But a kitchen needs focused task lights, while a hallway needs gentle ambient light.

- It Doesn’t Tell You Where to Put the Light: This is its biggest failure. Knowing you need 5000 total lumens doesn’t help you decide where to place the fixtures. This is why people fall back on a uniform grid, which, as we’ve discussed, is a poor solution.

I once consulted on a high-end apartment project where the electrical plan, based on a formula, called for 16 downlights in the living room. It was painfully bright and sterile. We created a much better result by removing half of the lights and repositioning the remaining eight to serve specific functions.

A Better Way: Count the Functions, Not the Area

My method is much simpler and more intuitive. Walk through the space, either physically or on a floor plan, and ask, "What needs to be lit here?"

- Count the Tasks: Where will you cook, read, work, or apply makeup? Each of these spots needs a dedicated task light.

- Count the Features: What do you want to look at? A piece of art, a beautiful plant, or a collection on a shelf? Each of these needs an accent light.

- Light the Paths: How do you enter and exit the room? You need a light by the door for safe entry. This is your ambient light.

By simply counting these functions, you will arrive at the number of lights you truly need. For example, in a bedroom, you might have:

- Two adjustable lights over the bed for reading.

- Two or three lights in front of the wardrobe to see your clothes.

- One light to accent a piece of art.

- One light near the door.

That’s a total of six lights, placed with purpose. The formula might have suggested eight or ten in a grid, which would have been excessive and less effective.

| Factor |

How It Affects the Number of Downlights |

| Ceiling Height |

Higher ceilings (>3m) may need more powerful (higher lumen) downlights or slightly more of them to get light to the floor. |

| Beam Angle |

Narrow beams (e.g., 24°) are for tasks. You’ll need more of them to cover the same area as wide beams (e.g., 60°). |

| Lumen Output |

A downlight with 800 lumens can be spaced further apart than one with 400 lumens. |

| Dimmers |

Using dimmers is essential. It allows you to "over-light" a space for tasks and then dim it down for mood, giving you the best of both worlds. |

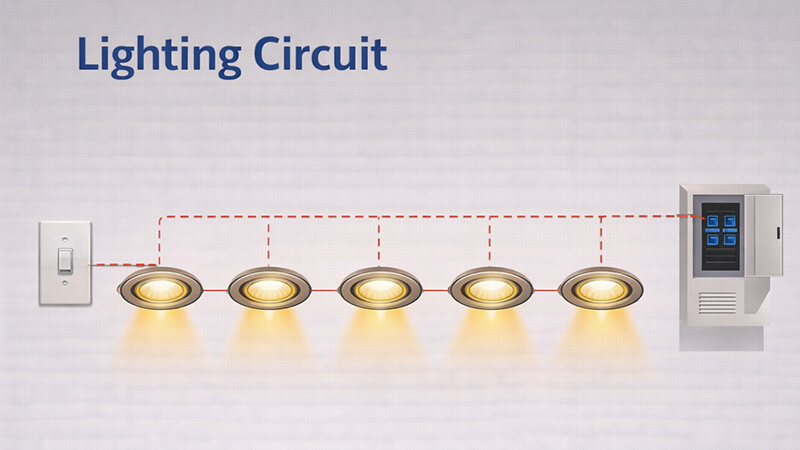

How many downlights can you put on one circuit?

Overloading an electrical circuit is a serious safety risk that must be avoided. It can lead to tripped breakers, flickering lights, or even create a fire hazard.

To calculate this safely, use the 80% rule. Find your circuit’s max wattage (Amps x Volts), take 80% of that total, and then divide by your downlight’s wattage. For example: a 15A x 120V circuit has a safe capacity of 1440W, which can run 144 10-watt LEDs.

This is a technical question that is absolutely critical for the safety and reliability of any lighting installation. For a purchasing manager or project contractor, getting this right is non-negotiable. The great news is that modern LED downlights are incredibly efficient, so the electrical load is much lower than it was with old halogen bulbs. However, you must still do the calculation correctly.

The Technical Calculation: Always Use the 80% Rule

Professionals never load a circuit to its maximum capacity for a continuous load like lighting. The National Electrical Code (NEC) and other international standards mandate using only 80% of the circuit’s capacity. This safety buffer accounts for heat buildup and prevents nuisance tripping of the breaker.

Here is the step-by-step process:

- Find the Circuit’s Total Wattage: Multiply the circuit breaker’s amperage (A) by the system’s voltage (V). In the US, this is typically 120V. In Europe, the UAE, and many other regions, it’s 230V. So, a standard 15A US circuit has a max capacity of 15A x 120V = 1800W.

- Apply the 80% Rule: Multiply the maximum capacity by 0.80 to find your safe load. For our 15A US circuit, this is 1800W x 0.80 = 1440W.

- Divide by Your Downlight’s Wattage: Look at the specifications for the LED downlight you are using. A typical modern downlight might consume 9W.

- Calculate the Maximum Number of Lights: Divide the safe load by the wattage of a single light: 1440W / 9W per light = 160 lights.

Here is a quick reference table for common scenarios:

| Region (Voltage) |

Circuit Breaker |

Safe Wattage (80%) |

Number of 9W LEDs |

| USA (120V) |

15A |

1440W |

160 |

| USA (120V) |

20A |

1920W |

213 |

| UAE/EU (230V) |

10A |

1840W |

204 |

| UAE/EU (230V) |

16A |

2944W |

327 |

The Practical Limit: Think About Control and Zoning

As the table shows, the technical limit is extremely high. You could technically put over 100 lights on a standard circuit. But just because you can doesn’t mean you should. The real-world limit is based on practical control. You would never want your entire house to turn on with a single switch.

For good design, you should group your lights into zones controlled by separate switches or dimmers. A good rule of thumb for residential projects is to have no more than 10 to 20 downlights on a single switch. This provides excellent user control and also helps manage "inrush current"—a very brief power spike that happens when many LEDs are turned on at the exact same time. While not usually a problem, having too many on one switch can sometimes trip a sensitive breaker. For any large project, always design your circuits around how the space will actually be used, not just the maximum electrical load.

Conclusion

In conclusion, perfect downlight placement isn’t about grids or formulas. It’s about placing light intentionally for tasks and features, creating a space that is both functional and beautiful.